On November 6th, 2015, Syrian artist Liwaa Yazji visited UnionDocs for the New York City premiere of her film HAUNTED (Maskoon).

HAUNTED is a portrait of exile. It captures the experience of displacement and profound uncertainty in the midst of Syria’s civil war. When the bombs fell, people escaped, leaving behind not only their homes but also innumerable memories. They were left with a physical and mental nowhere, a non-space between yesterday and tomorrow. Visiting this landscape via skype conversations and owner’s tours of their devastated residences, HAUNTED tells of the loss security and of the meanings that a home has in one’s life.

This screening at UnionDocs was supported by CEC Arts Link and the Vera List Center for Art and Politics, The New School, in conjunction with the exhibition and conference Abounaddara: The Right to the Image, presented at Parsons from October 22 through November 11, 2015.

UD:: Professionally you work in theater. You are a poet; and it is my understanding that this is the first time that you picked up a camera. What was the force that motivated you to start to work on this project?

Liwaa: online Yes, I come from a theater background, but it’s a tricky issue because in Syria we don’t have an audiovisual faculty. If you’re going to be involved in drama, whether it is TV, theater, cinema or radio even, you start in the theater faculty. Theater is not the form to really fulfill what I wanted for certain projects and ideas. I knew that for the ideas that I developed, I really need to go in with a camera. That’s where I started to educate myself. I went to visit friends on their shooting locations to start accumulating this kind of understanding and relation to the camera.

But I have to do it on my own. I had to learn a lot of things. I had to shoot, to work with the sound, to work as a producer: I had to work with everything – even the sculpting. I didn’t have a production manager with me, so I have to do everything on my own. It was a big motivation for me to just dive in.

UD: One of the things I admire formally about the project, is the way that it sort of collapses temporality. We have very little sense of time and progression. I am curious to hear, over how long did you shoot it?

Liwaa: The idea started in late 2011 and the archiving of stories started in 2012. Shooting started late 2012/ early 2013 and post-production started late 2013 until 2014. It was a very long process. I was not shooting every day. The situation in Syria was very difficult and I had to be very submissive to what was happening. Sometimes I am talking to people about going to do a shoot the next day, and then the next day they have gone to a different country, you know.

is urispas over the counter They have a different fate that I didn’t really have any control over – things were not under my control the whole time. I had to be very flexible. I was just telling Jason today that there are stories that I really wanted to have in this film, but the moment I went to the place the whole building was not there anymore. So, that was really important for me, sadly, and this is part of the process. The whole thing started out as a very personal question: What do I do if I am myself subjected to this question? What do I do, personally, if I have to leave my home? So that’s where it started. I started to talk to people before even telling them “I’m going to make a film”.

Whenever I go, I just sit with people. Everybody has a plan B and that was really very sad. It was a kind of pressure that everybody was denying in Damascus. Because, the situation still in Damascus is that you have the luxury to think about this idea. Some other cities don’t have the luxury to to even question: “what do we do?” – they just find themselves out in the street. So I started to see my extended family who live in a different city; I started to see that they are like, all at once fleeing without anything; and they have to start from scratch.

That was really like a nightmare for me, so I started asking people in Damascus. “What would you do if for example you went to work and you came back and the whole building was not there?” I started to pursue this idea, because it was giving me nightmares.

Then I started to archive stories. At the beginning I just wrote down stories because I thought: at a certain moment you really need to have this kind of archive. It’s also a psychological archive of how people are acting and how surreal the situation is; you know, you go to a house, somebody is talking about the weather in Sweden, and just like, studying the flight plans, how to run away, how to pack your bag. So, it was very surreal; people are living here – one foot here and one in no-man’s-land. It took a very long time in the process of preparing until I reached the moment where I could build bridges with the people that were moving.

UD: In some ways, the film feels like a crowd-sourced project in the sense that many different sections are shot with many different cameras, through Skype, DSLR-footage, cameraphone footage; and at times where there is no footage. There are still photos. I would think it was coming from many different sources. Is it all coming from you? How do all these different camera choices point to the logistics of shooting this project and putting it together?

Liwaa: Actually, I didn’t have permission to make the film. I started to make the film in Syria in the areas that are still under control of the regime. So, that means I am moving secretly; I am not allowed to do this. But it’s not a secret anymore — I already did it. At that moment I had to hide everything I carried with me. For example, I am having a camera that I borrowed from someone on the other side of the checkpoint and then I do a shoot in that area. I pack up stuff, and take back my stuff and find a way to smuggle it through the checkpoint.

So, sometimes when I get to the area, I really cannot bring the camera in. It depends on the whole technical issue of security. Sometimes when I’m not allowed even to have my camera with me, I leave Purchase it behind. Knowing that I just need to shoot this person, there is no other way than using the mobile phone.

I have had better situations when I went to Lebanon to shoot there, but not far better. Actually, because the people in the camps are afraid, they are not free. They are also afraid of being shot, if they — you know there are secret agents — yeah, the whole security question was the issue. With the Skype couple, I really wanted to be there, but being under siege, we went immediately to what is possible. Sometimes we were only 2 km away, but I just couldn’t get there.

Muhammad who is in the film shared a lot of the Skype meetings with the people. We lived together with them. We were also under siege with them. And, really, the question of technical issues was the last thing, you know, when you want to get something… whatever is there. Twice I had the luxury of having a DOP, but not the luxury of having light equipment or sound equipment. Also, it was kind of aggressive to go into the camp with all this equipment to see how miserable people are.

Audience comment: Pills buy allicin capsules at walmart This film brought back the question of how contingencies dictate what you see. If you had one camera it would have been a very different, and probably a much less interesting and complex piece of work. But we actually see, when you describe the process, you actually see it was cobbled together because it had to be cobbled together. That becomes the aesthetic.

Liwaa: That’s exactly what happened. Also, sometimes I had to make the decision: if I did not have a camera with me, would I go and shoot? – I would say “no, I will go and shoot even if I….“ [don’t have anything but my mobile phone]. I remember once we were in Beirut. We wanted to shoot people living on the street. They were so afraid just to even see the mobile phone. So we went and talked to them.I didn’t have the chance to take out a camera or anything because the mobile phone was frightening for them. So, we asked them if we could just have some words, because we wanted to communicate. In that moment, we put everything away, and just spent time talking to them. Sometimes you forget about the whole project and you approach reality as a person; you forget that there is something else that should be done in that moment.

UD:: Your comment about hearing media narratives about hundreds of thousands of Syrians migrating to Sweden, for example. You’ve talked about how to produce alternative forms of representation to mainstream or broadcast representations of the ongoing war in Syria. Could you talk more about how you consciously approached this project in opposition to other forms that are circulating?

Liwaa: It was also another risk; I also got used to seeing Syrian people as stereotypes in media, TV and films, and even in normal life. There is now all of a sudden a stereotype to fit in as a Syrian. You are a refugee or pathetic. As if we have been born like that. All the history and culture is gone and you just have a stereotype left of… let’s not analyze what is the stereotype.

So, when I started doing this, this was not actually in my mind, but it was very clear that I would not go to the narrative that I am used to: which is talking about politics, political stands, and mainly about being pathetic. You are not crying for losing the houses. If we are crying in this film, we are crying because we want to make fun. “Take a tissue” – the Syrian spirit. I was very conscious that I would not have the film include dead bodies, or deformed people. I did not want to have Syrians as numbers. It’s stories that I can identity with. If you see hundreds of people dying you wouldn’t identify with them.

My colleague from Abounnadara said,: “You look at them in TV, you don’t recognize faces, (…) you don’t feel any kind of relation to them. It could happen to them but not to you. But if you look in the eyes of somebody you can identify yourself with, you understand him more and you feel more that you could be in his shoes.” So, that was very conscious for me. I didn’t want to have anybody who is lamenting pathetically or saying what we hear on the news. I wanted to escape from this.

UD:: That position also was stated in the prologue of the film. One of the subjects, who I think has an iPad open –we are not really given the context— but we get the sense that he is watching Youtube footage of something horrible and then he shuts it off.

Audience question: How did you get access to the country?

Liwaa: I can still go to Damascus. One of the protagonists is still in Syria, and that is a big responsibility for me.

Audience question: The protagonists all seemed to be in various forms of shock. They were negotiating reality on a day to day basis. How did you cross paths with your protagonists; are they people you knew already? What led you to the people that you ended up picturing?

Audience question: The protagonists all seemed to be in various forms of shock. They were negotiating reality on a day to day basis. How did you cross paths with your protagonists; are they people you knew already? What led you to the people that you ended up picturing?

Liwaa: Some of them were acquaintances of others. Some I just met at a certain time in 2012 in Damascus. I started to get to know people that I didn’t know before. Because maybe they are the only ones left in that avenue, my circle of acquaintances started to change. Social circles are different. There is immediately a new code between people. We are here. We are under the same pressure. There is a kind of “Yes, I didn’t know you before, but I know how you are passing your days – I am doing the same.” So, in a way, some of them are my friends. I also got to know people to whom I developed this kind of curiosity – towards their stories. The choice of what is in the film, what is outside the film, depended on the film itself, on the artistic choices of the variations of the idea of home. If I shot somebody who did not want to show his face, I could not force him to be in the film. Also, the artistic choices of the form itself.

Audience question: I’d like to hear more about the structure of the film. The editing is so elegant and there is so many evocative moments of transition. What principles did you lay out for yourself? toradol street price

Liwaa: The very first shot of the film where we are looking at the building in front of us – it is just like a shaky mosaic of looking at somebody else’s life. I knew from the very beginning that I wanted to go for fragments. That was the beginning of my idea that you are looking at the building, that everything is shaking and you have one glance here and one glance there. The electricity here is high, some places are red, somebody is shaving, somewhere someone is doing the dishes. Then you go back to the same room, where it is empty. So that kind of looking at a building in front of you, you are kind of looking at life, while it’s — I don’t want to be pessimistic — while it is fading. The last moments of looking at something is not always fixed, it is not always clear. Depicting different lives. But there is one destiny.

Audience question: Is there any way for us to understand the people that were continually trying to leave from the part of Damascus that was under the regime control?

Liwaa: It’s very complicated. Where they live is exactly the bordering line between the battlefield and Damascus. So the battlefield, that is, what is called the frontier, the outskirt, where the city ends and the suburbs start. There is a very tricky situation in Damascus, because from one side they belong to the so-called “everything-is-normal” zone. From the other side, they belong to the war. At one point, before the siege, they were still under this kind of hazy situation where they can go to work, but they cannot stay late. They have some kinds of food, but not everything. They can live, but this is not a life. So, they are still on the borders of being in-war and out of war. That all changed once they were under the siege.

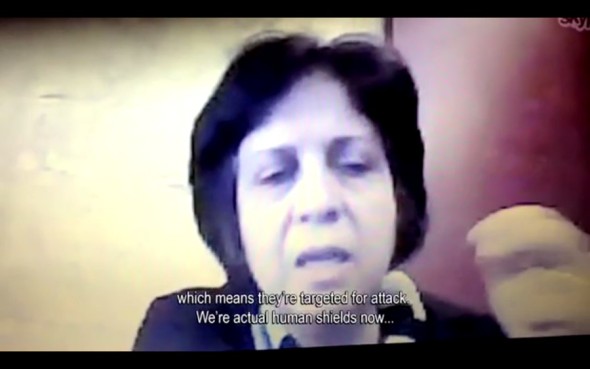

The free army or the opposition took over a little bit more, and so the regime laid siege to this area; people were not allowed to go outside. The area was being bombed. So, people wanted to run away, but they couldn’t. The opposition cannot use heavy weapons because, for one they didn’t really have them, but also because the civilians in that area are their families and neighbors. So, in this case, the regime was stronger. They wouldn’t let people escape the area. That is why she says “we are used as human shields”. That was the situation: they don’t want to leave, but they have to leave. I understand the confusion, because every two kilometers has a different stories now in Syria. So, this is story of living on the border.

Audience question: I wanted to ask about ideas about distribution – is it already distributed across Europe?

Liwaa: Yes, I have a distributor, and the film is screened at festivals. I appreciate that it has this exposure, because I feel some kind of a mission to screen it as much as I can. I always welcome possibilities of screening and my distributor understands the idea completely. She is not going more with the money issue rather than with the ethical issues. She’s very flexible with this. I have offered my film to many free screenings. I started to understand the kind of questions that the film raises, and I feel I have a mission to get this message out to as many people as possible. I guess, so far, the film is doing rather well and I am looking forward.

UD:: Going back to a previous comment about geography. No particular geographies are ascribed to individuals in the film. Individuals are not identified by name. The editing is not very causal. Can you talk about those editorial decisions that have a rather profound shape on the final work?

Liwaa : I felt like any mentioning of geographical locations is something that would also contribute to providing different stereotypes. I wanted to take out the stereotype as much as I could, so I can leave the stories of the people. That was on purpose. There is a sentence somewhere when you see a destroyed car, and I just say “is this your car?” I knew that you don’t know who I am asking this question – but is it important? I guess that the image is much more important than finding out who’s car this is. That was a very essential approach. Does it really matter whether he lives in Damascus or in Tartus? Would it makes any difference for you? Or would it make a stereotype? It would answer what you really know about the city. So then you will impose something rather than hearing what he is saying, that was something I really didn’t want, because sometimes that creates political stereotypes. Let’s say, if someone is living in Tartus it means that he is most likely to be with that regime. If you are still living in Damascus, would that mean, for example, that you are still with the regime? So all these kinds of analyses I wanted to cut off. That was the approach, really just to listen to them and what they are saying rather than helping to fill in the gaps.

UD:: Are you planning to go back to Syria? What is your next project? How will having made this project affect your ability to start a new project?

Liwaa: I still go to Syria. I try to defend this right and the advantage as much as I can. I might not be able to hold it for a long time, but I will try. For a long time, I used to work from Beirut, then back to Syria. I have been moving back and forth. I have to think about where to go next. I have another project, but I have to also be reasonable because it was supposed to be in Aleppo. I am just giving myself some time, because now Aleppo is under siege and the situation there is very bad. I want to go there to make a film, not just to jump into a battlefield with no reason and with no calculation of the situation. Right now, I cannot go there. So basically, right now I am just on stand-by. Yes, the film might make things more difficult for me, but I have to find solutions because I have no answer. In this moment, if I go back to Syria, I still can go. I have several ideas to start from, but I prefer to go to the idea I am more passionate about and unfortunately it is in a place that is not possible to enter at the moment.

I would like to say thanks to all the people in the film. The film is them. The effort of everybody and the trust of these people. It was a matter of life sometimes.

I would like to thank them as a filmmaker. prazosin buy uk

—-

Liwaa Yazji was born in Moscow in 1977. She is a graduate of Theater Studies in Damascus/Syria and worked in the fields of theater dramaturgy, playwriting, and screen writing. She acted in Abdullatif Abulhamid’s September Rain (Syria 2009) and was assistant director of Allyth Hajjo and Ammar Alani’s docudrama Windows of the Soul (Syria 2011). In 2012, she published her first play “Here in the Garden” and is currently preparing the second one with the Royal Court. In 2014, her poetry book Peacefully, we leave home was published in Beirut. She wrote the screen play for the TV drama series The Brothers (2013) which was broadcast on Abu Dhabi TV, CBC Egypt, and LBC Lebanon. Haunted (Syria/Germany 2014) is Liwaa’s directorial debut.

The Vera List Center for Art and Politics

Founded in 1992 and named in honor of the late philanthropist, the Vera List Center for Art and Politics at The New School is dedicated to serving as a catalyst for the discourse on the role of the arts in society and their relationship to the sociopolitical climate in which they are created. It seeks to achieve this goal by organizing public programs that respond to the pressing social and political issues of our time as they are articulated by the academic community and by visual and performing artists. The center strives to further the university’s educational mission by bringing together scholars and students, the people of New York, and national and international audiences in an exploration of new possibilities for civic engagement. www.veralistcenter.org